Frank was cracking jokes while drinking with his friends the night before he hanged himself on a trellis in front of the house.

After finishing a few bottles of beer, Frank left the group to talk with his uncle who had been taking care of him since he lost both of his parents.

Dinner was about to start when he arrived. Frank grabbed a plate, took a huge serving, and sat next to his uncle.

It was unusual because Frank never sat beside his uncle. He always seated himself at the other end of the table where he could easily take off to avoid long conversations over meals.

He showed his uncle a photograph of a girl and said he wanted to marry her.

The older man was not aware that Frank was trying to express something that was bothering and consuming him.

Early that day, he had a heated argument with his girlfriend who broke up with him because of another man.

Frank did not tell his friends about what transpired. He tried to hide the sadness and disappointment by telling funny stories while he was with them.

He also did not have the chance to tell his uncle who was rushing out for a business meeting after dinner.

The next day, at about 4:30 in the morning, the uncle found the lifeless body of Frank hanging on the trellis.

In his pocket were three packs of cigarettes, a lighter, and the photograph of the girl.

“It shocked all of us because we knew him as a funny and extroverted person,” said Lorraine who studied in the same school with Frank.

Frank killed himself more than a decade ago but Lorraine recalled his story after she was diagnosed with depression several months back.

“He was the first person who came into my mind when the doctor told me that I am suffering from depression,” she said.

The 36-year old call center said she was trying to understand why and how Frank ended up “in that situation.”

The trigger

In May, Lorraine contracted the new coronavirus disease and manifested mild symptoms, which brought her into isolation.

She had to send her daughter to the province “because no one will look after her while I am recovering from the disease.”

After more than two weeks, her company sent her for another COVID-19 swab testing to determine if she was fit to go back to work.

The test result indicated that she was still positive with the disease. She was advised to take another 14-day self-quarantine.

“It was during that time that I started to feel anxious. I can’t explain why, but I was too worried about too many things,” she said.

Apart from her husband, who stayed and took care of her, Lorraine has no one to talk with because she decided to keep her condition secret.

“I was afraid that people would discriminate me and regard my family with contempt because I got infected with COVID-19,” she said.

She said she started to lost her appetite, not because of COVID-19 “but because of extreme sadness that suddenly attacked me any time of the day.”

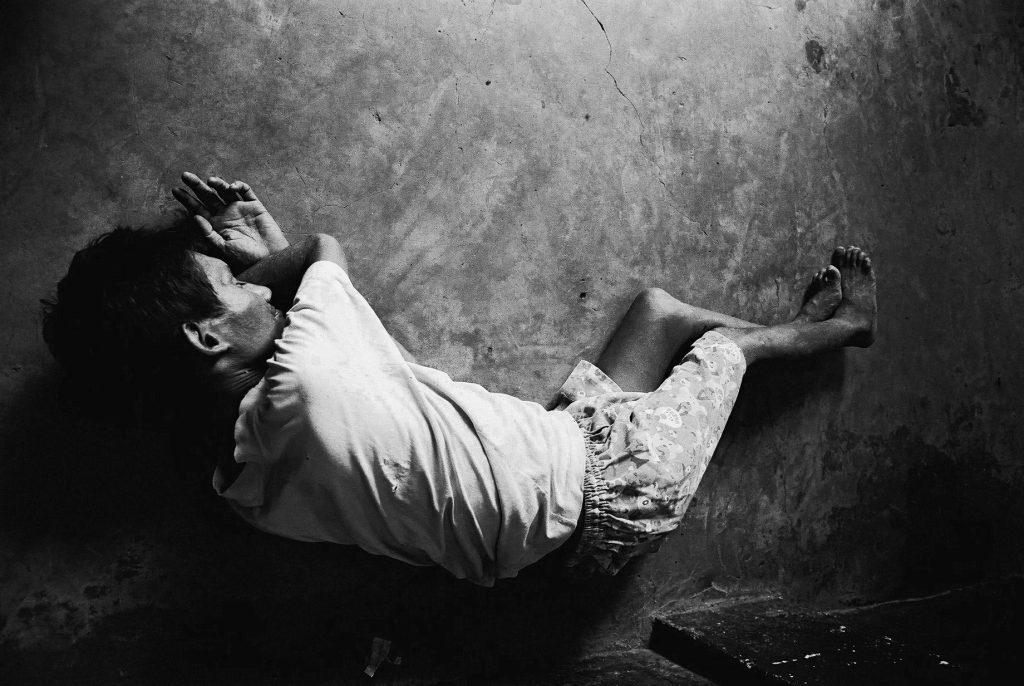

The worst night came when she began having thoughts of “just dying” to escape from the feeling of being alone and to “put an end to all those anxieties.”

That was the time she decided to seek professional help.

Lorraine called a hotline that offers medical consultations to people who suffer from anxiety attacks, depression, and other mental health issues.

A few days later, she visited a mental health expert to “better understand” her condition and learn how to emerge from it.

The spike

Not everyone who suffers from mental distress due to COVID-19 has the chance or “the clarity of mind” to immediately recognize the problem and seek help.

Last week, a lawyer from the country’s Public Attorney’s Office died after jumping from the sixth floor of a hospital building in the capital where he was being treated for COVID-19.

In the city of Cebu, a 48-year old male coronavirus disease patient committed suicide by jumping off from the third floor of a hospital in June.

The country’s health department on August 26 announced that the number of people seeking help for mental health rose since the start of the pandemic.

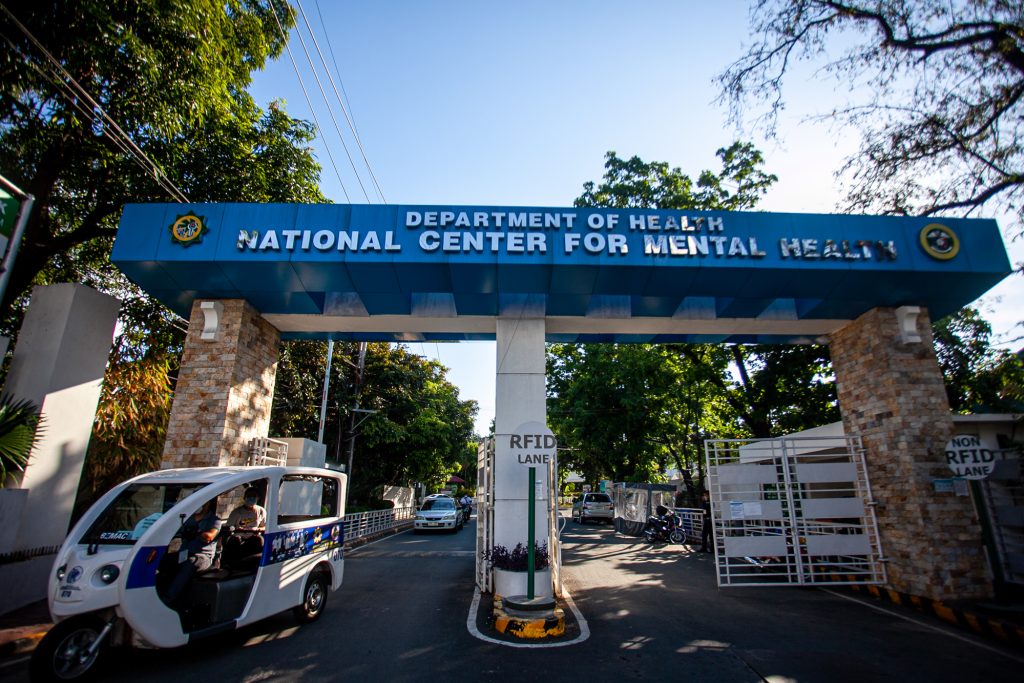

Since April, the National Center for Mental Health has received more than 1,000 phone calls from people seeking professional help from just 400 monthly calls before the pandemic.

From 672 calls in March, the mental health institution received 1,104 calls in April. The highest spike so far was in June when it received 1,115 calls.

Church response

As early as March, various church institutions and faith-based organizations have set up mental and spiritual online consultations for people who need professional help.

The Order of the Ministers of the Infirm in the Philippines, also known as the Camillians, opened its official social media account for people to directly talk with priest counselors.

Father Dan Vicente Cancino said the pandemic has “greatly affected” people’s mental and spiritual wellbeing, “especially those who are in the front lines and people who are sick.”

The priest, who is executive secretary of the health care commission of the bishops’ conference, said his congregations program aims to give support to people who are “overwhelmed with fears and anxiety.”

Father Cancino said people who suffer from mental health issues need someone to talk with, adding that a phone conversation is already a big help “to boost their morale and spirit.”

Like the new coronavirus disease, mental health issues have no boundaries and can affect anyone regardless of social and economic status, gender, religion, or profession.

Father Victor Sadaya, CMF, executive director of Porta Coeli Center, an institution that provides “psycho-trauma” management and pastoral counseling, said the crucial step in dealing with a mental health problem is “recognition.”

“The person must recognize and admit that he or she is going through a problem and that he or she needs help from other people,” he said.

The Claretian priest said another important element in combatting mental health illnesses is the “support system.”

“The support system can start in the family, with the person’s circle of friends, or they could find it in some organizations that extend support to mental health patients,” he said.

Father Sadaya said the Church can also serve as a support system for people who need a venue to express or to draw strength and motivation from.

The priest, however, said the Church as an institution must be prepared in initiating programs aimed at helping people combat mental health problems.

He urged dioceses and parishes to come up with a “mental health program” to assist individuals, including priests, who suffer from mental and spiritual distress.

Father Sadaya called on the public to seek a deeper understanding of mental health and address the issue with proper assessment and treatment.

“A mental health problem is not a death sentence. No one must die because of depression or trauma or anxiety. We can cure it but it will require the involvement of the whole community,” said the priest.

Source: Licas Philippines

0 Comments