Sept. 28, 2020. Again, and quite lamentably, President Rodrigo Duterte conducted one of his late-night press conferences. As usual, he rattled on and on about issues big and small, mostly irrelevant to the more pressing problem of the pandemic.

Covid-19 remains the country’s foremost concern. An average of 5,000 Filipinos infected daily is not a trifling matter. We’ve been under varying levels of lockdown in all of six months since March, the longest quarantine period all across the region.

Then, in the middle of wandering off the point came what I had somehow expected from the beginning: a rant against Facebook. Last week, the social media engine took fraudulent accounts to task, shutting them down for spreading “fake” news.

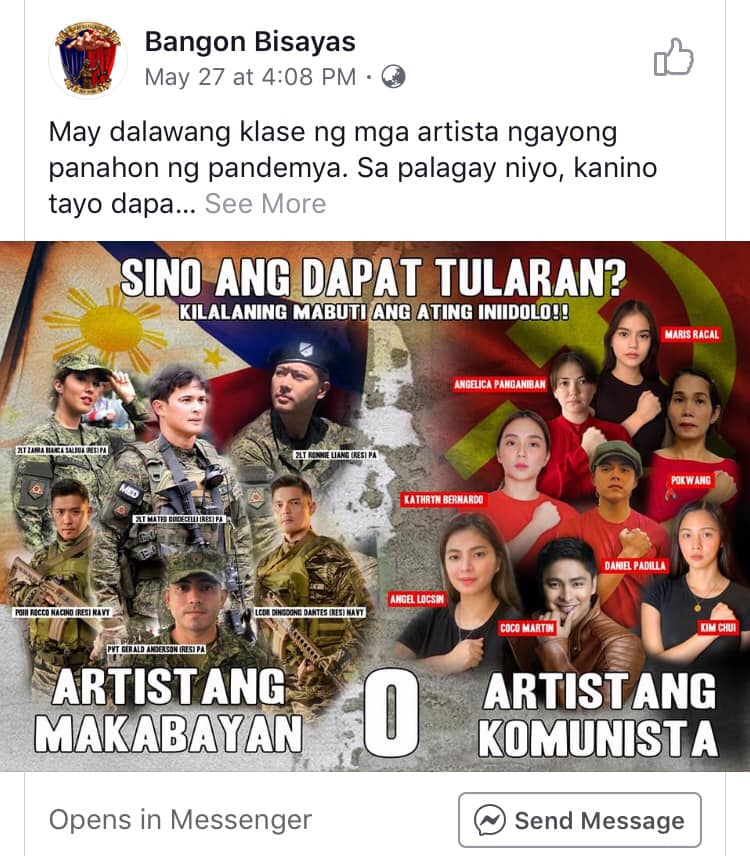

These included accounts allegedly belonging to the Philippine military which were used to allegedly red-tag critics. “Red-tagging” or “red-baiting” is the practice of accusing someone of being either a communist or a terrorist.

On Sept. 25, Rambo Tabalong of Rappler reported on a certain Army Captain Alexandre Cabales who was said to have been managing fake Facebook accounts, based on the findings of the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab.

The report said that Cabales “served for a decade in the Davao Region, the home region of President Rodrigo Duterte,” and was assigned in the 10th Infantry Division (ID) from 2008 to 2017. This was based on a text message to Rappler by Army spokesman Colonel Ramon Zagala.

Cabales’ profile includes graduating from the Philippine Military Academy in 2008. “Early in his career, Cabales was a combat soldier, becoming a platoon leader from 2008 to 2012, and then a company commander from 2012 to 2014 for the 28th Infantry Battalion, which is still under the 10th ID. From 2014 to 2015, Zagala said Cabales became a Civil Military Operations (CMO) officer,” the report said.

The Philippine military top brass responded swiftly to the shutdown of the social media sites, claiming these were “advocacy groups” under the lookout of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP). Military spokesperson Maj. Gen. Edgard Arevalo spoke to the Inquirer on Thursday and demanded for the reinstatement of the sites.

“Arevalo said Gen. Gilbert Gapay, the chief of staff, asked Facebook head of public policy in the Philippines Clare Amador in a meeting on Wednesday whether they could restore specifically the Hands Off Our Children (HOOC) page. He did not identify the other groups, saying only that they were ‘of similar advocacies like preventing child exploitation and trafficking of minors, and combating terrorism,’” the Inquirer added.

Abroad, The Guardian reported on the fake Philippine social media accounts, describing these as “coordinated fake accounts with links to individuals in China and in the Filipino military that were interfering in the politics of the Philippines and the US.”

Facebook also said that all the accounts were either based or linked to “two distinct networks based in China and the Philippines”.

“[These] were removed for violating its policy against foreign or government interference, which it defines as ‘coordinated inauthentic behavior on behalf of a foreign or government entity,’” the report added.

The Guardian added, “The China-linked accounts, pages and groups on Facebook and Instagram used virtual private networks to cloak their location, to spread targeted content in south-east Asia and particularly in the Philippines, where their posts were tracked by more than 130,000 followers.”

Duterte, as expected, made no secret of his contempt towards the shutdown of the military-managed sites by the social media giant. In his recent press conference, he tackled it with the same incautious behavior as the rest of the issues involving the military.

Duterte made several claims that night: (1) that Facebook is a social media application where people can post anything they want if only to create trouble for the administration (calling it a Pandora’s Box) and associating criticism with insurgency; (2) that the social media giant has shut down a government advocacy site; and (3) that the presence of Facebook in the Philippines is predicated on President allowing it to operate and letting the administration use it for its own “advocacies”.

Duterte said, “What would be the point of allowing you to continue if you cannot help us? We are not advocating mass destruction, we are not advocating mass massacre. It’s a fight of ideas. And apparently from the drift of your statement or your position, it cannot be used as a platform for any… It is so convoluted. I cannot understand it.”

The problem with this statement is that it has a serious disconnect from what is happening on the ground. A number of these sites have been used by the military and the police to red-bait government critics, accuse them of being communists and terrorists, and by doing so exposed them to serious risks of intimidation and harassment, even murder.

Phil Robertson, deputy director of the Asia Division of Human Rights Watch, said “The military and police, along with other government agencies, have for years been ‘red-tagging’ Karapatan. And the reality is that people who are ‘red-tagged’ are at heightened risk, including of being targeted for killing. This includes Karapatan’s secretary-general, who herself has been subjected to ‘red-tagging.’”

Lawmaker Sarah Elago, a representative of the Kabataan Partylist, a political party serving the Filipino youth, had been red-tagged more times online than probably any personage within the circle of Duterte’s critics.

In one instance, Rep. Elago was the subject of “fake” news claiming that she was arrested for “recruiting communist rebels”. Her photo was altered, the post by “Ang Aking Bayan” Facebook site shared and reshared thousands of times.

The accusation, however, was nowhere near being fact. Truth be told, the photograph used by the fake Facebook site was found to have been copied and altered from an original post made by Elago after calling for the release of 18 relief operations volunteers, two of whom were campus journalists. Agence France-Presse did a fact check of the fraudulent post.

As early as 2018, Facebook has been on a hunt for sites spreading fake news and hate speech. Some of the sites which were blocked earlier were Duterte News Today, Duterte News Info, FilipiNews, HotNewsPhil and PhilNewsPortal.

In an interview with half-a-dozen paid trolls operating in the Philippines, The Washington Post said “They are dramatically altering the political landscape in the Philippines with almost complete impunity — shielded by politicians who are so deep into this practice that they will not legislate against it, and using the cover of established PR firms that quietly offer these services.”

I’ve been an active member on Facebook since the last quarter of 2008. I have witnessed in more ways than I can claim how the police had used their social media accounts either to spread fraudulent news or accuse someone of being a communist.

As a journalist and writer, I and my writings have been the target not only of fake news accounts loyal to Duterte, but baseless accusations from websites supporting his presidency.

Fellow journalists have been threatened with rape, assassinations. They were and still are being insulted and threatened in more ways than media institutions could track them down and draft a list of these social media sites.

Duterte has turned Facebook into a weapon, leaving his critics on the defensive against a social media blitzkrieg aimed not only at discrediting journalists and critics, but putting them in harm’s way.

These troll accounts operate with impunity and make a literal killing by pushing government critics in harm’s way. In fact, an Oxford study places the cost of operating a troll army at US$200,000 dollars (P10 million). You can freely download and read the Oxford Study here.

I’m a firm believer in the freedom of speech and of the press, even to the extent of holding literary tools such as sarcasm and satire as sacrosanct. I believe in the exchange of ideas, the battle for hearts and minds, however fierce.

But under a political dispensation where false claims and baseless accusations coming from government fake news websites put the critic in harm’s way, even murder, there is reason to be on guard.

But Duterte’s strong-arm tactic will not work. He is caught between a rock and a hard place, to put the cliché succinctly. The social media application has been his troll’s cyberspace platform for the last four years.

Duterte hinting of shutting down Facebook in the Philippines could gravely damage a troll army operation which, in truth, has overstayed its welcome. Furthermore, it has already cost his administration an arm and a leg in annual costs.

Shutting Facebook down will introduce him to a world of hurt from which there can be no recovery.

Joel Pablo Salud is an editor, journalist and the author of several books of fiction and political nonfiction. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official editorial position of LiCAS.news.

Source: Licas Philippines

0 Comments