Self-harm is not a topic I’m particularly fond of writing. I’m no expert in mental health, thus I am in no position to offer expert advice. What I am is an eager student of the behavioral sciences, having been a Psychology major in college.

Even today, one of my chief preoccupations outside of the writing of journalism and literature is to bury my face in books penned by Carl Jung, Albert Camus (The Myth of Sisyphus) and other authors who dealt with the subject of self-harm.

A personal story

As a teenager, I’ve had serious bouts with pathological rage. I was diagnosed in high school as manic depressive with a predilection to self-harm and harming others. Growing up, I wrestled with thoughts of suicide. One December night, I decided to cross the line and made my first attempt. Good thing the gun jammed.

Now three years shy of being a senior citizen, I still wrestle with this unrelenting death wish. My modest triumphs are predicated on a decision I made long ago: to look at the lives of other people and see where I can lend a hand. Many live lives several lashes more tragic than my own. Looking outside myself for fulfillment helped me manage the raging demons inside me. But I cannot speak for others who struggle with the same.

No-Suicide Contract: What is it exactly?

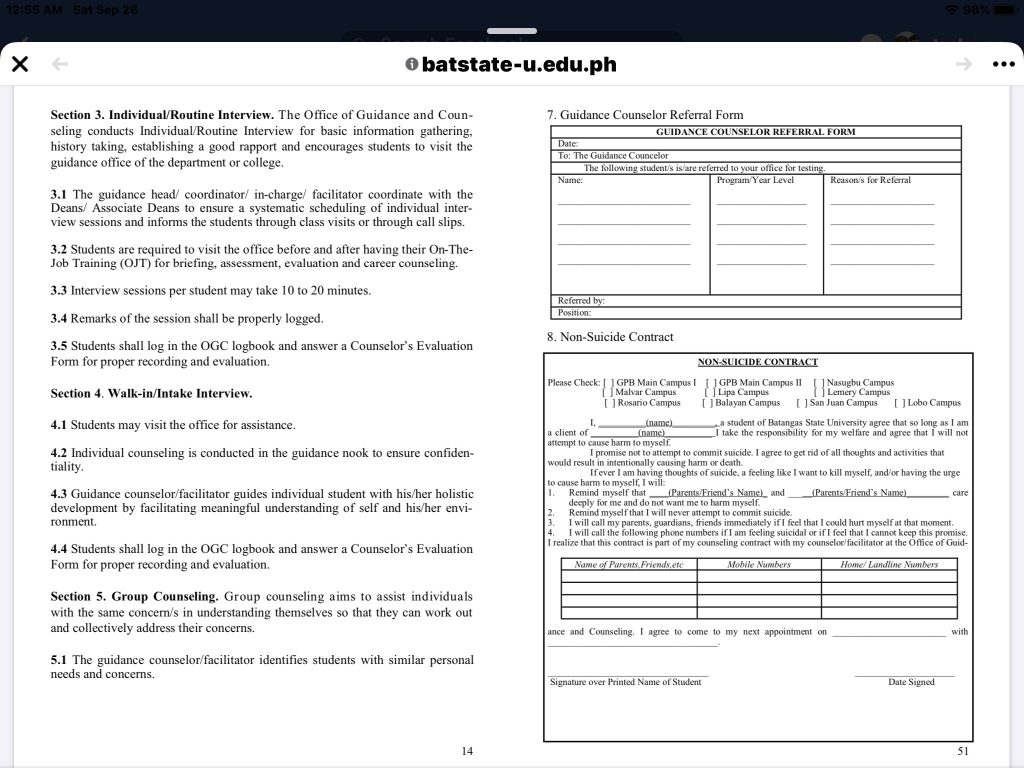

My interest in writing about suicide today was triggered by a document sent to me by a social media friend. It carried the logo of Batangas State University and was titled “No-Suicide Contract”.

The document carries fundamentally the assertion of the signatory students that they will be responsible for their own welfare “and will agree that I will not attempt to cause harm to myself”.

My first thought was to confirm if it really came from the said university. How easy it is to fake a document these days given the multitude of computer applications to use. Some in Facebook were kind enough to lead me to the Batangas State University (BSU) official website where the “contract” can be found.

I rushed to do some digging on the matter of No-Suicide contracts. One website, Suicide.org, explains that “no-suicide contracts are not legal documents […] The first and most important section of no-suicide contracts is the unequivocal agreement that the individual signing the contract will, under no circumstances, die by suicide. Then the next section lists names and phone numbers that an individual needs to call if he or she becomes suicidal.”

The website was quick, however, to stress that “a no-suicide contract is not a substitute for assessment and treatment. All suicidal individual should be professionally assessed and treated immediately. Again, a no-suicide contract is one additional tool that may be used in conjunction professional treatment.” It is neither legally binding nor compulsory.

In the end, the website makes the assertion that “everyone should clearly understand that using a no-suicide contract in no way guarantees that an individual will not die by suicide.”

Healthy Mind Manila

I got in touch with a good friend and fellow author Ramil Digal Gulle, who also sits as founder of the Facebook site, Healthy Mind Manila.

He explained that No-Suicide Contracts is meant to be “therapeutically binding”.

“For some people, having them enter into a tangible ‘contract’ promising not to self-destruct, it has some therapeutic effect. Essentially, it’s a commitment and a promise to seek help whenever suicidal ideations and impulses occur.”

He was quick, however, to stress that “It is not, however, suitable for all persons who may be going through suicidality. Remember, these people being handed this ‘contract’ are usually not in their best state of mind. So even in a legal sense, they’re not fit to sign any legal document, right?”

Gulle also added, “When I read the ‘contract’ handed out by BSU, it seems that it’s not something handed out to all students. It seems it is something that a guidance counselor might ask a student in distress to sign. But like I said, such a contract should be viewed more as a therapeutic tool that is meant to shore up a suicidal person’s willpower to survive.”

I was able to confirm this through a student of BSU who said it’s not a requirement of the university to sign the contract.

Gulle also underscored the importance of expert advice and treatment in addressing the problem of suicides in schools. “On its own, divorced from other therapeutic tools, a non-suicide contract is a flimsy tool. It has to be part of an overall treatment plan.”

Based on the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) age-standardized suicide data, as per 100,000 population in the Philippines from 2000 to 2016, the average suicide for males spiked from 4.5 to 5.2 while females from 1.8 to 2.3.

Globally, around 800,00 take their own lives. That’s one person every 40 seconds, according to WHO. Based on a Rappler report using the 2015 WHO Global school-based survey, “Among 8,761 students from Grades 7-9, Year 4 in the Philippines: 11.6% among 13 to 17 year olds considered suicide, 16.8% among 13 to 17 year olds attempted suicide.”

The stigma related to suicide makes it difficult to exactly quantify the numbers on a year-on-year timeline, let alone make an accounting of attempts. Much of the data are based only on reported cases.

Handle with care

While I can easily understand the intention of anyone in drafting the No-Suicide Contract, I find the contract itself rather incongruent with the demands of the medical condition, if at all it was meant to address the condition properly and with some efficiency.

At first glance, the document seems quasi-legal, the wording much too callous and detached to even remotely suggest a thorough understanding of the medical condition on the part of the school’s guidance counselors.

A contract better suited to address the problem should’ve been penned along the lines of a personal note: for the university to vow to be there and walk the student through the dark moments, using all the time, resources, and know-how at the school’s disposal. An extensive scientific program dealing with the medical condition ought to first be in place.

Signing a contract which leaves the welfare of the students in their own hands—students who presumably not in the healthiest of mental states—seems absurd at the very least.

Granted that No-Suicide Contracts are not legally binding, calling it a “contract” heaps untold pressure on the student because he signs his name on a document that pressures him to look after his welfare and be in charge of behavior over which he has no full control.

Gulle said, “This is why, to me, such non-suicide contracts must be handed out very judiciously and with much analysis and deliberation in our Filipino context. Because such contracts may just add to the anxiety and pressure already felt by the suicidal young person. Culturally, we really don’t like documents. This aversion has cultural roots. As for members of Healthy Mind Manila, none of our members agreed to non-suicide contracts. In their minds, it doesn’t help. But maybe for some Filipinos, it can. But I’ve only met one or two Pinoys who signed one.”

One netizen, however, raised a good question: won’t the signing of the contract give the teachers or professors a false sense of security? It’s a good question. After a student signs the contract, teachers and professors might do away with any attempt to “see the signs”.

Compassion is still the best medicine

Popular though it may be to some, a No-Suicide Contract may not be what the students need to stop themselves from self-harm. Based on several studies, stress stands as the number one cause of suicide.

Perhaps, as we face a new “normal,” schools can better serve their students by keeping the stress levels down to a manageable level, teaching them how to cope as things get more challenging.

But more than anything, the academe must go out of its way to bridge the cold space between the schools and the students through more compassionate methods. Extending a personal hand—promising to be there for the beleaguered child come hell or high water—can go a long way in saving a child’s life.

Joel Pablo Salud is an editor, journalist and the author of several books of fiction and political nonfiction. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official editorial position of LiCAS.news.

Source: Licas Philippines

0 Comments