The morning of Nov. 23, 2009. By and large, a red-letter day.

My wife had just won first prize in a national literary contest for the novel in Filipino. That day, we set off to grab the reward money and certificate during the ceremonies scheduled in Makati City at nine.

My wife and I left the post-ritual chitchat an hour early to don another hat, this time as journalists. It was too early to stick around for whiskey.

The newsroom of the now defunct online news portal, Dateline Philippines, was already packed when we arrived. Editors, reporters and photojournalists jammed a long dinner table full of laptops, smartphones, digital cameras, and every other gadget needed for the coverage of the day’s news.

It was business as usual until a call arrived sometime before lunch. The details were yet too sketchy, but one thing was assured: on the road to Shariff Aguak in Maguindanao that day, a massacre had taken place. Hitherto unconfirmed were the number of journalists who were murdered.

The newsroom fell silent. These were colleagues, some friends.

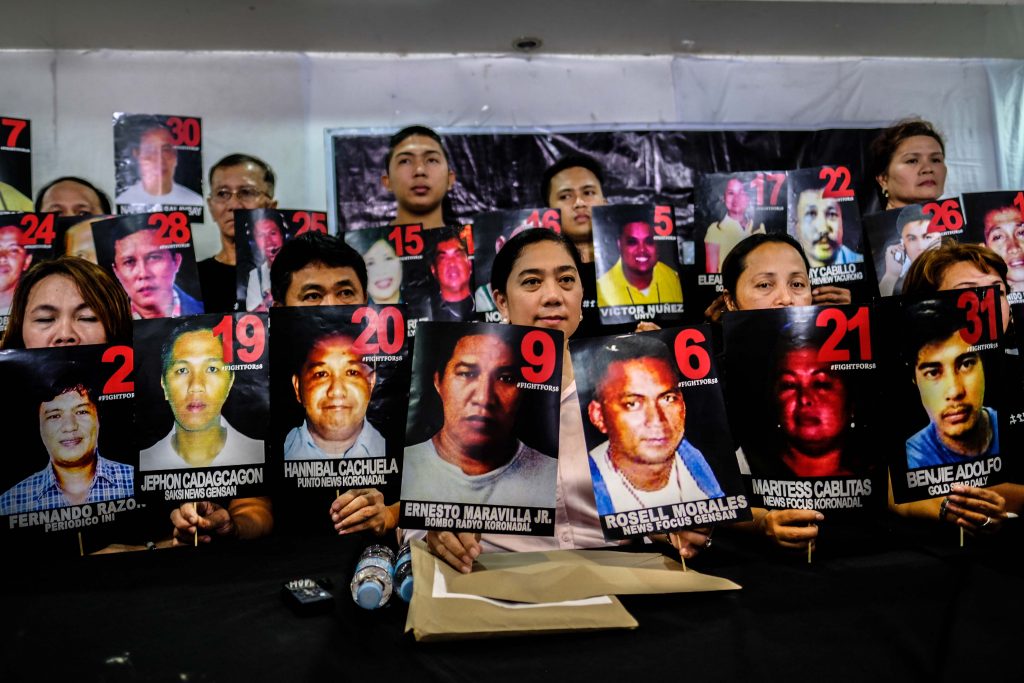

In the course of a couple of weeks, investigations revealed that 58 people, including 30 media workers, died in what was to be dubbed the worst election-related violence in the history of Philippine polls.

The suspects: the Ampatuan clan, the most feared warlords in all of Maguindanao, including 200 of the family’s 5,000 henchmen.

News of the investigations and eventual capture of mastermind Andal Ampatuan Jr. and his father hogged the headlines for months. As a result of public indignation, then President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo—a close ally of the Ampatuan clan—declared martial law in Mindanao.

Under the Arroyo presidency, the Ampatuan clan and its henchmen served as the government’s “private army” and “vigilante group,” sowing fear at the very heart of a community largely entombed in poverty.

The Human Rights Watch 2010 report on the brutal massacre, “They Own the People: The Ampatuans, State-Backed Militias, and Killings in the Southern Philippines,” said “The massacre—the worst in recent Philippines history—has since been attributed to members of the Ampatuan family, which has controlled life and death in Maguindanao province for more than two decades through a “private army” of 2000 to 5000 armed men comprised of government-supported militia, local police, and military personnel. Many members of the family, which is headed by Andal Ampatuan, Sr.—Maguindanao’s governor from 2001 to 2009—hold official posts in the province and region. Before the 2007 elections, most of Maguindanao’s 27 mayors were the sons, grandsons, or other relatives of Andal Ampatuan, Sr., including his son, Andal Ampatuan, Jr., who stands charged with 57 counts of murder in connection with the 2009 massacre.”

In the course of our coverage of the investigations, our editors noticed a startling shift in the Ampatuan narrative. Some news from the countryside began labeling the Ampatuan henchmen as “freedom fighters.” From where this claim had come from, we don’t know.

The strategy was clearly aimed at “lowering” their sentences should they be found guilty in court as “rebels fighting for their liberty” and not as common criminals.

Our chief editor noticed this pattern in a couple of news reports and began instructing us to stick to the facts: that the men who committed the crime were criminals belonging to a government-backed militia, and not freedom fighters. Thanks to our editor’s sharp eye, the false narrative soon fell into disrepute.

On Dec. 19, 2019, the court passed a guilty verdict on the remaining Ampatuan clan and its private army. As court cases of this nature go, the verdict is now up for appeal.

By all standards, the case is far from over, having 80 more suspects, 15 of them belonging to the Ampatuan clan, yet at large, including one more principal suspect. They must all be tried even after a decade of court battles.

Fast-forward to the fourth quarter of 2020. All so suddenly, in a series of reports filed by Duterte’s government media in early September, Unesco was quoted as classifying the Ampatuan massacre as “resolved”. The Duterte administration used it as proof, however flimsy and laughable, that the incumbent government is dead set on championing the freedom of the press.

As a response, on Sept. 12, several organizations, private individuals and members of the media (including my wife and myself) sent a letter to Unesco explaining why this should not be so.

“It is unfortunate that UNESCO’s conclusion appears to have relied solely upon government claims, without consideration for the other facts and contexts surrounding the case—a glaring oversight, considering that many of us have good relations and work closely with your agency’s Jakarta, Bangkok, and other offices.”

The letter adds, “Lest it be forgotten, of the 188 journalists killed in the Philippines since 1986, 16 have lost their lives under President Rodrigo Duterte, who has not bothered to hide his disdain for free and independent media. Duterte led the charge to shut down ABS-CBN, the country’s largest broadcast network. His government continues to hound independent online news outfit Rappler and its founder and CEO Maria Ressa with dubious legal cases. His national security advisers have incessantly tagged news outfits and journalists who have criticized the government as allies or pawns of ‘terrorists.’ This is a particular source of concern, in view of the recent enactment of the draconian Anti-Terrorism Law. We hope that UNESCO will not play into the attempts to ‘sanitize’ the reputation of the Duterte government among international agencies in view of the pending scrutiny of the President by the International Criminal Court.”

A week later, Unesco overturned its initial classification, saying the organization will reclassify the massacre as “unresolved”. It was a triumph of swift and clear thinking.

A letter from Unesco’s Deputy Director-General Xing Qu said, “Unesco learned in early Sept. 2020 that, in this particular case, appeals have been launched. Based on this new information, the legal cases concerned will, therefore, maintained as ‘ongoing/unresolved’ in the Unesco Observatory of Killed Journalists, as well as the ‘Director-General’s Report on Safety of Journalists and the Danger of Impunity’ until such a moment when a final verdict is reached by the Philippine Judicial System.”

These two cases of shifting narratives on one burning issue—the Ampatuan massacre—which transpired across two presidential administrations, point to a systematic government campaign out to derail the national memory.

It is no secret that Duterte is a known ally of Gloria Arroyo, with Atty. Salvador Panelo—legal counsel for the Ampatuan clan—standing as Duterte’s former spokesperson.

For journalism to remain relevant in this day and age of alternative truths, it must now go beyond the restrictions of objectivity—which is often mistaken as neutrality—and analyze the facts for that they truly are.

Revisionism is as old as humanity’s ventures into war. Lies serve as a war implement out to disrupt, dislocate, even disembody the facts so as to confuse the enemy. Despots had used disinformation to leave the public unable to make informed decisions, keeping any possibility of unrest or revolution at bay.

However, an objective approach to facts do not carve a clear picture of what is happening. A journalist worth his salt must be able to string the facts together for these to make sense, using context and historical backdrop to paint a clearer, larger picture.

Every tree must be seen in light of the forest and the ecosystem which surround it.

This core necessity in the work of journalism cannot be overstated now that revisionism and alt-truth are becoming more and more the norm rather than the exception. While the principle of objectivity and fairness remain significant to reportage, the same reportage must itself evolve based on where evidence leads it.

In short, reportage in the day and age of alt-truth must in no way stand on the fences of objective exposition.

Rather, it must serve as a brazen road sign pointing to what we’ve been in search of all along: the truth.

Joel Pablo Salud is an editor, journalist and the author of several books of fiction and political nonfiction. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official editorial position of LiCAS.news.

Source: Licas Philippines

0 Comments