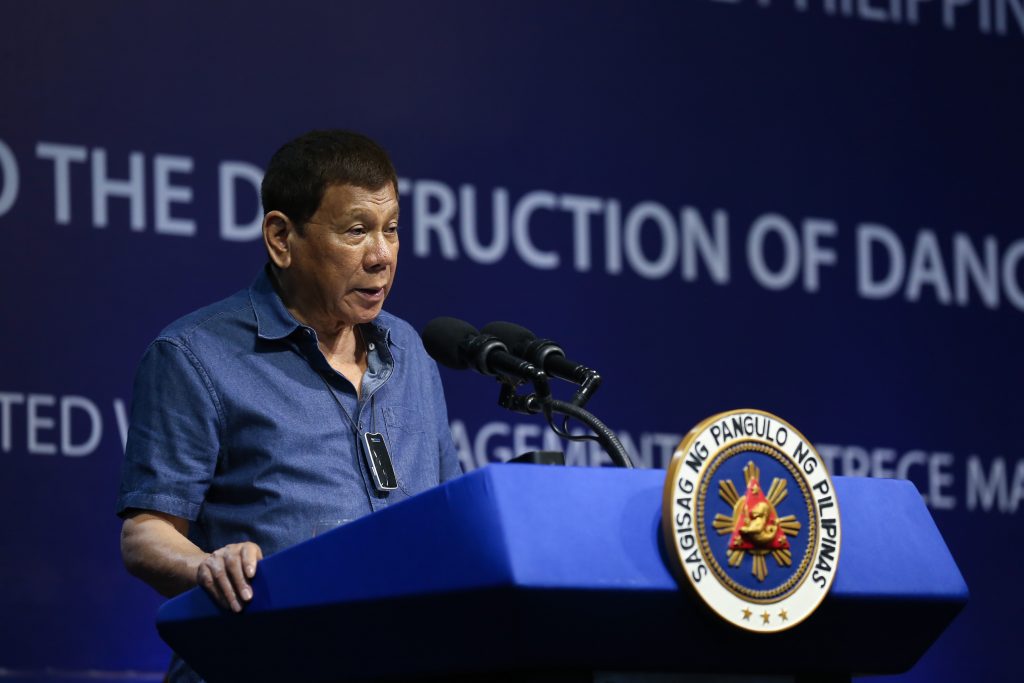

President Rodrigo Duterte has long defied human rights as any autocrat would do.

While to Duterte’s paid sycophants, something so preposterous is nothing new, we who struggle for our rights have all reason to fear it. His latest outburst in Cavite adds to the list of violent rants aimed not only at suspected drug users, but human rights advocates as well.

The Philippine Star headline of Dec. 3 roared like an ill-tempered train yanked of its breaks: “‘I don’t care about human rights,’ Duterte says, urging cops to ‘shoot first’”.

In Duterte’s upside-down world, human rights advocates like myself are nothing more than terrorists. And as terrorists, we are better off dead.

Allow me to quote the Philippine Star report: “‘All addicts have guns. If there’s even a hint of wrongdoing, any overt act, even if you don’t see a gun, just go ahead and shoot him,’ he said in Filipino. ‘You should go first, because you might be shot. Shoot him first, because he will really draw his gun on you, and you will die.’”

Here, Duterte outlines a plot for his officers to swallow without question, a plot so disconnected from reality that to call it “speculative” is to sin against the genre.

He added, “Human rights, you are preoccupied with the lives of the criminals and drug pushers. As mayor and as president, I have to protect every man, woman, and child from the dangers of drugs. The game is killing…I say to the human rights, I don’t give a shit with you. My order is still the same. Because I am angry.”

Let’s deal with this one misshapen idea at a time.

All addicts have guns. One dangerous facet of this unwarranted generalization is that Duterte assumes the worst in people, more so those who fall in the crosshairs of government suspicion.

What his statement does is normalize condemnation and the imputation of a charge which, by and large, can only be garnered with some accuracy through due process. Without due process, it’s a hoax at best.

Time and again, we’ve seen how government had chosen to dispense with due process as an excuse to cut to the chase. This utter disregard for this legal component in establishing guilt only makes it impossible for anyone to make heads or tails about who they are pursuing, whether they are, in fact, addicts or not.

Now, combining the charge that someone, despite proof, is a drug addict, and that all such addicts carry firearms, it not only instills fear among officers of the law, but it forces them to use their firearms despite the absence of provocation.

This is Duterte telling them what will happen even before it happens, to the end that it will now control their actions.

What is worse is that real drug peddlers now have reason to arm themselves given the direct order by Duterte for cops to shoot first. This, more than anything, endangers the lives of police officers, those suspected without proof of guilt, and authentic peddlers of illicit substances.

The statement serves as a trap, a deviously contrived verbal apparatus which triggers a cycle of violence wherein both the police and the suspect—guilty or not—fall as the victims of Duterte’s bloodlust. The gullible pitted against the utterly helpless.

If there is anyone guilty of putting the lives of officers at risk of being killed during police operations, it is Duterte himself.

Duterte’s claim that human rights advocates “are preoccupied with the lives of the criminals and drug pushers” is a blatant fabrication. Without proof of guilt, there is no telling whether those being pursued are lawbreakers or not.

It, therefore, makes no sense to charge human rights advocates as promoters and protectors of criminals. For how can these advocates even know if those who are being hunted down are criminals in the first place?

What rights advocates are promoting is a person’s legal right to face his or her accusers in a court of law, to be proven by his or her accusers as either guilty or not. In short, the person’s right to have legal closure of the case in question.

The principle of presumption of innocence balances the authorities’ exercise of power with the legal rights of the accused. This serves as a safety net not for the guilty but the innocent. Last I looked, by virtue and power of the 1987 Constitution, we are still a democratic republic regardless of the fact that we have a tyrant sitting in Malacañang.

The game is killing. These four words form the political schematics not only of Duterte’s “drug war” but his overall leadership doctrine. To him, it is a sport of provocation, of competing as in a chess game. Where each move sets off a spiral of events which, if we’re not careful, can plunge the country into irreparable chaos.

Consider the brutal killings of human rights activists. Who can say that after a change in administration, if at all that would happen, that this threat would stop? That those who now enjoy near-to-perfect impunity would soon be caught?

Take the Hacienda Luisita massacre. Were any of those responsible for the brutal dispersal of United Luisita Workers Union workers in 2004 ever caught? Isn’t it true that those guilty of the murder of activists remain in power all across several presidential administrations? Some of whom were even promoted, so I heard.

As I listen to Duterte’s words, I can’t help but wonder: with this administration kicking up the ante several notches with its bogus drug war, Terror Law, and run-amuck killings where police had been involved, would the next administration—considering they’re from the opposition—be any better at curbing impunity?

While we can hope for the best, that same hope has left us utterly dissatisfied through the years. By the looks of it, we now have little choice but to actively participate in the shaping of our political lives. It is up to us—the public—to make a move as to how we can turn the tide in our favor.

It’s important that we document everything. Every killing. Every peso lost to corruption. Every bit and tad of excess this administration indulges in. Resibo, ika nga. In our own little way, we must list down their names, their participation in the crimes. Mark their signatures in the laws which oppress the people.

This is our best offensive: to keep the country as well as the world informed of this regime’s crimes and shenanigans.

Likewise, every article, every essay, every piece of reportage and literature exposing their crimes should be shared on social media over and over until it goes viral. Let’s not stop at “liking” them and commenting on the posts. Sharing information would serve the purpose of getting our stories told.

If trolls can act as one solid unit in their campaign to spread Duterte’s fraudulent narratives, we can do that, too, with the facts as well as the truth. In our fingertips lies the technology that can help us drown out the lies.

We’ve gone past fighting merely for our rights. As I have said before, we’re in a struggle for our very lives.

And should the chance to build a better government than what we have now finally arrives, know this: whatever progress we’ll achieve in this regard must come with the recognition that change is only possible if we, the people, participate in it wholeheartedly and without the least bit of hesitation.

As for journalists, this is not the time to out-scoop one another. We need not play that game for now. This is the time to look the devil in the eyes and hold the line—as witnesses to the unfolding of history.

Until then, we who defiantly push against the trampling of our rights must first come together and agree to push back as one.

Only then can real change be possible.

Joel Pablo Salud is an editor, journalist and the author of several books of fiction and political nonfiction. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official editorial position of LiCAS.news.

Source: Licas Philippines

0 Comments