He could not see the guns pointed at him, but he felt the boots on his back and head.

Jojo de Leon’s face was on the ground while his house was being demolished in a farming community in Buntog village in Hacienda Yulo, Calamba town, south of Manila.

There used to be at least 65 houses in the village but only six remained at the end of 2020.

On January 9, only one small grass hut survived after armed men destroyed all the houses, a move, De Leon said, aimed at evicting the farmers from the land.

“The first attack this year happened on January 6,” he narrated. “They will not stop until everyone leaves the land,” he said.

Sitio Buntog is part of the disputed 7,100-hectare Hacienda Yulo, which spans the cities of Calamba, Cabuyao, and Santa Rosa in Laguna province.

A large portion of the disputed land has already been converted to residential communities.

“Thousands of farmers have already been displaced, but we choose to fight for our rights to our lands that we inherited from our ancestors,” said De Leon.

The 45-year-old farmer said a land developer plans to convert the farming village into a gated subdivision and a golf course.

De Leon’s great grandparents settled in the area from Talisay town in Batangas province after the eruption of Taal Volcano in 1910.

“They pulled the weeds, cultivated the land, planted trees and crops,” he said.

Government records show that the 100-hectare piece of land that De Leon’s great grandparents and other settlers were tilling was originally owned by the Madrigal family.

Eddie Billiones, chairperson of an organization of farmers, said the Madrigal family allowed the settlers to stay and till the land with a condition that the farmers will make the land productive.

In the early 1920s, the area was occupied by the Americans who established a sugarcane plantation, later known as the Canlubang Sugar Estate.

The area’s highlands were not occupied by the estate, allowing De Leon’s great grandparents and other villagers in Buntog to continue tilling the land.

After the Americans left the country, Jose Yulo, the caretaker of the land, took over and exacted taxes from the farmers, said Billiones.

Years later, the farmers decided to pay taxes to the government, hoping that the land would be transferred to their names.

In the 1980s, farmers in what was known as Hacienda Yulo started organizing themselves to ask the government and the Yulo family to distribute the land to the farmers.

“Many families decided to accept money and leave the land because they did not receive any support from the government,” said De Leon.

De Leon’s family, however, decided to stay and continued their claim on the land.

In 2010, armed men threatened to evict the farmers who barricaded the village, resulting in a stand-off that ended in violence.

In August 2020, armed men entered the village and burned down three houses.

Shrinking space for farmers

The latest incident forced De Leon to temporarily leave the village and seek protection after receiving “death threats.”

“Everything is uncertain now,” he said. “We know that there will be another wave of attack to force us to permanently leave.”

He said if only the government listened to the issues raised by the farmers in the past, “the situation could have been better.”

In 1991, the government denied a petition to include Hacienda Yulo in the country’s Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program.

The Department of Agrarian Reform earlier determined that the land is “highly suitable” for agriculture.

A report released by the agency’s regional office, however, said the coconut, coffee, and other forest and fruit-bearing trees were planted by farmers “hired as agricultural workers.”

De Leon maintained that the trees were planted by the settlers, including his great grandparents, who cultivated the land since 1910.

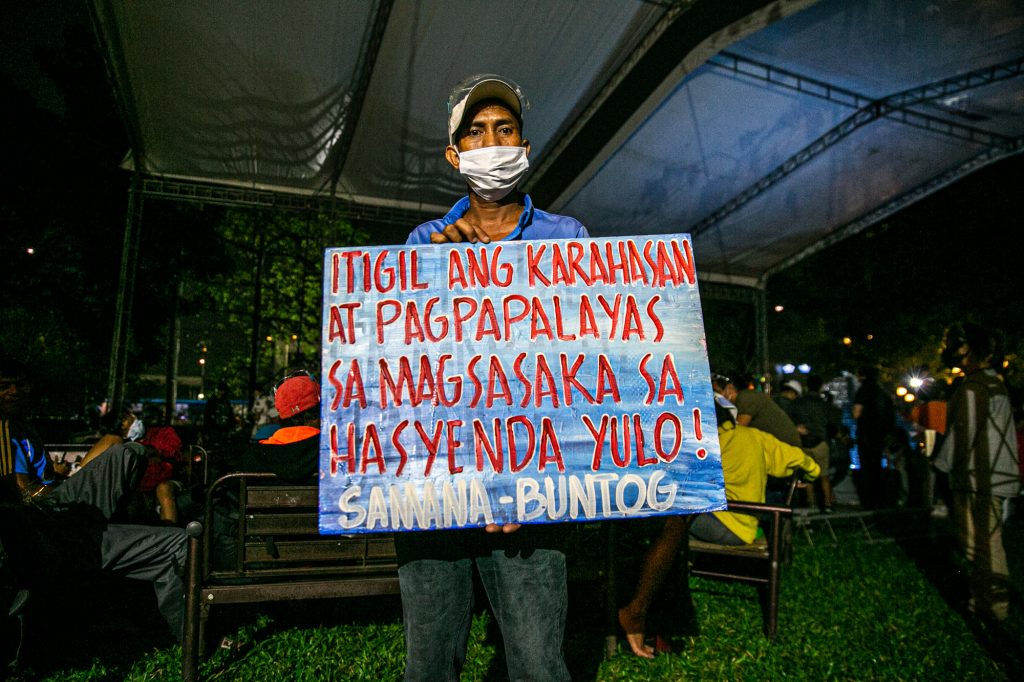

On January 20, De Leon went to the Philippine capital to seek a dialogue with the government agencies.

“We just want to appeal to the government to reconsider our petition and include Hacienda Yulo in the government’s agrarian reform program,” he said.

Deteriorating land rights condition

Farmers’ groups said the situation of the peasantry in the country has never improved.

More than three decades after protesting farmers were killed in the gates of the presidential palace on January 22, 1987, “farmers are still the poorest people in the country.”

“We are still fighting for our rights to land. We are still at the mercy of a bogus land reform program,” said peasant leader Billones.

Father Rolly de Leon, co-chairperson of the Promotion of Church People’s Response, said the government seemed to not have learned from the lessons of the past.

He said that instead of addressing landlessness, government agencies “tend to neglect the rights of the tillers” and “only answer to huge business interests.”

The priest said local agriculture is a dying industry because of massive land grabbing and land-use conversions, the influx of imported products, and the lack of national programs for the sector.

Peasant and rights groups have been pushing for the passage of a law that will cover vast landholdings, including Hacienda Yulo, and distribute the land for free to farmers.

The government, however, rejected the proposal.

Government data show that 120,889 hectares of land were already distributed to 77,275 agrarian reform beneficiaries nationwide from July 2016 to June 2019.

At the beginning of the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte in July 2016, there were undistributed 613,327 hectares of land.

During the time of former president Fidel Ramos, the government distributed a total of 1,113,019 hectares of land to beneficiaries, or an average of 371,006 hectares yearly.

The administration of former president Corazon Aquino was able to distribute 452,074 hectares from 1988 to 1990, for an average of 150,691 hectares annually.

Former president Joseph Estrada distributed a total of 379,905 hectares from 1998 to 2000 or 126,635 yearly.

Land distribution is at its lowest during the time of Duterte.

Source: Licas Philippines

0 Comments