Second of Three parts

First Part: Not a land of savages: The people Magellan met in Samar and Cebu

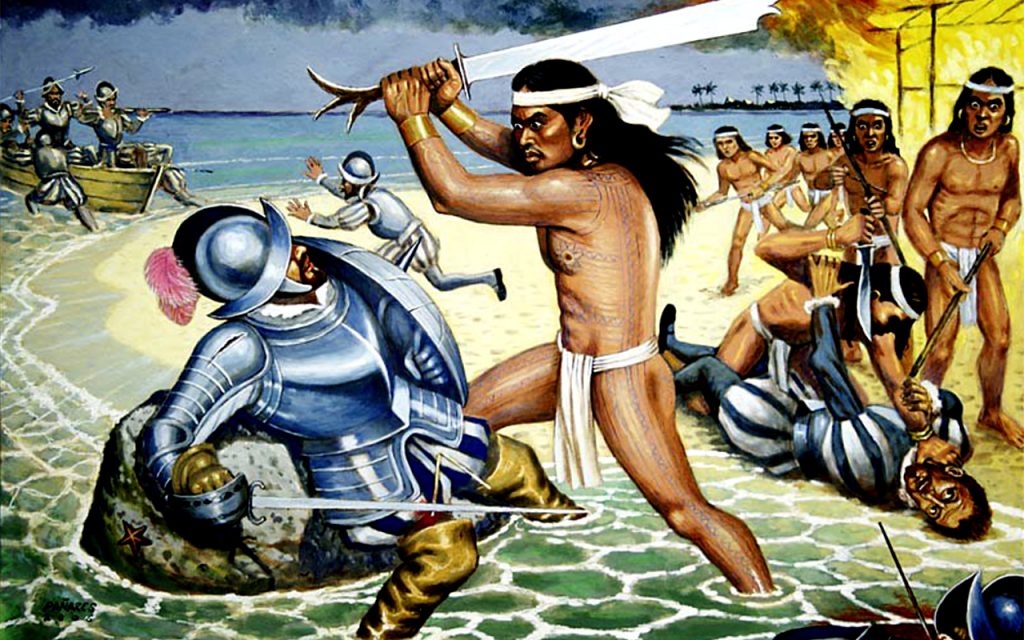

All these years I have always imagined the battle between Ferdinand Magellan and Cilapulapu on the shores of Mactan as a kind of class struggle. The poor and hapless indios versus the obscenely powerful and rich Spaniards.

By all means it was a test of courage for both sides, the little David of a far-off region in the largely uncharted East pushing back against the superior firepower of the Goliath of the armada of Spain.

Little did I know that the Italian scholar Antonio Pigafetta who witnessed the battle firsthand had quite a different story to tell.

The day was April 7, 1521. After having landed in Samar and Homonhon, meeting the chieftains there, an entourage from Magellan journeyed to Cebu to offer his friendship to the chiefs of the villages. As was the foreigner’s custom when docking at the port, they announced their arrival by firing their artillery. Pigafetta noticed how greatly it affected the people, to the extent that they all ran to their local king (chieftain) for succor.

“When they reached the city, they found a vast crowd of people together with the king,” Pigafetta wrote, “all of whom had been frightened by the mortars. The interpreter told them that that was our custom when entering into such places, as a sign of peace and friendship, and that we had discharged all our mortars to honor the king of the village.”

After the chieftain was reassured of the entourage’s intentions and said that they had come at a good time, he immediately laid out the custom of his own kingdom, mainly that all visitors—foreign or domestic—should pay the chieftain tribute.

As proof of the chieftain’s power and influence, the chieftain cited the arrival of a ship from Siam which docked but a mere four days ago, bringing gifts of gold and slaves. In fact, the same merchant from Siam had remained in the village to trade the remaining gold and slaves which he had brought with him.

Magellan’s interpreter responded with a threat, confident of the superior authority of Magellan as the representative of the Spanish king. “These men are the same who have conquered Calicut, Malaca, and all India Magiore [India Major]. If they are treated well, they will give good treatment, but if they are treated evil, evil and worse treatment, as they have done to Calicut and Malaca. The interpreter understood it all and told the king that his master’s king was more powerful in men and ships than the king of Portogalo, that he was the king of Spagnia and emperor of all the Christians, and that if the king did not care to be his friend, he would next time send so many men that they would destroy him.”

Regardless of the threat, the chieftain said he would deliberate with his men and would give the interpreter an answer the next day. As a sign of the chieftain’s hospitality, he invited them to a sumptuous meal of meat and wine served in porcelain platters.

To reinforce Magellan’s offer of friendship, the friendly chieftain of Mazaua arrived in Cebu, a respected senior among the natives of several islands, and tried to persuade the chieftain of the courtesy being shown to him by Magellan.

The chieftain succumbed to the offer of the captain-general. To seal the friendship, a blood compact was staged. The next day, the nephew of the chieftain, who was prince, together with the king of Mazaua and the interpreter, arrived at the Trinidad to make their peace.

During the course of the meeting where Magellan presided, the prince reassured the captain-general that he and the king of Mazaua had authority to make peace. Pigafetta noted that as the prince spoke of peace, he prayed to God to confirm it in heaven.

“The captain seeing that they listened and answered willingly, began to advance arguments to induce them to accept the faith,” Pigafetta wrote.

Magellan proceeded to speak to them about “God who made the sky, the earth, the sea, and everything and that He had commanded us to honor our fathers and mothers, and that whoever did otherwise was condemned to eternal fire; that we are all descended from Adam and Eve, our first parents; that we have an immortal spirit.”

Appealing now to their free agency in his sharing of the message of the gospels, Magellan invited the prince, the chieftain of Cebu and all the people to convert to Catholicism, appealing more to their free agency than their fears.

“The captain-general told them that they should not become Christians for fear or to please us, but of their own free wills and that he would not cause any displeasure to those who wished to live according to their own law, but that the Christians would be better regarded and treated than the others. All cried out with one voice that they were not becoming Christians through fear or to please us, but of their own free will.”

The prince, however, entreated Magellan that he would have to first bring the message to the chieftain before the offer of baptism was to be done. After an exchange of gifts, the peace was sealed. Magellan’s entourage, together with the prince, proceeded thereafter to meet the chieftain in his palace where he, his family and people finally agreed to be baptized. In the middle of the city square, a cross was erected by Magellan’s men. The converts were also instructed to burn their idols.

The next seven days proved challenging to Magellan. While much of the population agreed to be baptized, there were villages who refused to obey. According to Pigafetta, Magellan’s men burned down one hamlet because they refused to be converted.

So much for an appeal to free agency.

Anyway, days later, Zula, one of the chieftains of Mactan, sent two of his sons to pay tribute to the foreigners. The two reiterated their father’s desire to send the captain all that he had promised him. There was, however, one small problem: a defiant chieftain named Cilapulapu.

While Pigafetta failed to elaborate as to why Magellan decided to engage Cilapulapu in battle, it may well be deduced that he probably wanted to prove his worth to the chieftains who chose to convert. That he was a man of his word, willing and able to summon the powers at his disposal to protect those now under the rule of the king of Spain.

“When morning came forty-nine of us leaped into the water up to our thighs, and walked through water for more than two crossbow flights before we could reach the shore […] When we reached land, those men had formed in three divisions to the number of more than one thousand five hundred persons. When they saw us, they charged down upon us with exceeding loud cries, two divisions on our flanks and the other on our front. When the captain saw that, he formed us into two divisions, and thus did we begin to fight.”

Not only was Magellan outnumbered well-nigh thirty to one, Pigafetta said the natives refused to stand still. As such they were able to dodge bullets from muskets. Their armaments, including huge shields, protected them from all the weapons wielded by Magellan’s men, including crossbows.

To terrify the native warriors, Magellan ordered their houses to be razed. It failed to have the desired effect because it enraged the natives more.

“Two of our men were killed near the houses,” Pigafetta wrote, “while we burned twenty or thirty houses. So many of them charged down upon us that they shot the captain through the right leg with a poisoned arrow. On that account, he ordered us to retire slowly, but the men took to flight, except six or eight of us who remained with the captain. The natives shot only at our legs, for the latter were bare; and so many were the spears and stones that they hurled at us, that we could offer no resistance.”

Those who were left to defend Magellan fought for an hour until a bamboo spear had lodged itself into the captain-general’s arm, and a scimitar, a thin curved sword, a cut on his left leg.

“That caused the captain to fall face downward, when immediately they rushed upon him with iron and bamboo spears and with their cutlasses, until they killed our mirror, our light, our comfort, and our true guide. When they wounded him, he turned back many times to see whether we were all in the boats. Thereupon, beholding him dead, we, wounded, retreated, as best we could, to the boats, which were already pulling off.”

According to Pigafetta, the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan fell on Saturday, twenty days after landing in Cebu. Eight of Magellan’s men were killed that day, including four Christian natives who fought alongside the captain-general. Only 15 of Cilapulapu’s men fell during the battle.

If we were to base it on Pigafetta’s account, the battle wasn’t so much a paradigm of class struggle but a show of force between two established and wealthy dominions—Spain and Cebu. Dominions with their own culture, tradition, pride, power, and experiences in trade and battle. It seems Magellan had totally underestimated the muscle of majestic Mactan.

While other chieftains welcomed Magellan and Catholicism with open arms, let’s not forget that the defiant chieftains were as formidable a force as those from imperial Spain.

Spain’s return to the islands would soon usher in 300 years of colonial rule. The spirit of Cilapulapu, however, lived on.

Joel Pablo Salud is an editor, journalist and the author of several books of fiction and political nonfiction. He is also a member of the Philippine Center of International PEN and heads the Committee on Writers in Prison. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official editorial position of LiCAS.news.

Source: Licas Philippines

0 Comments