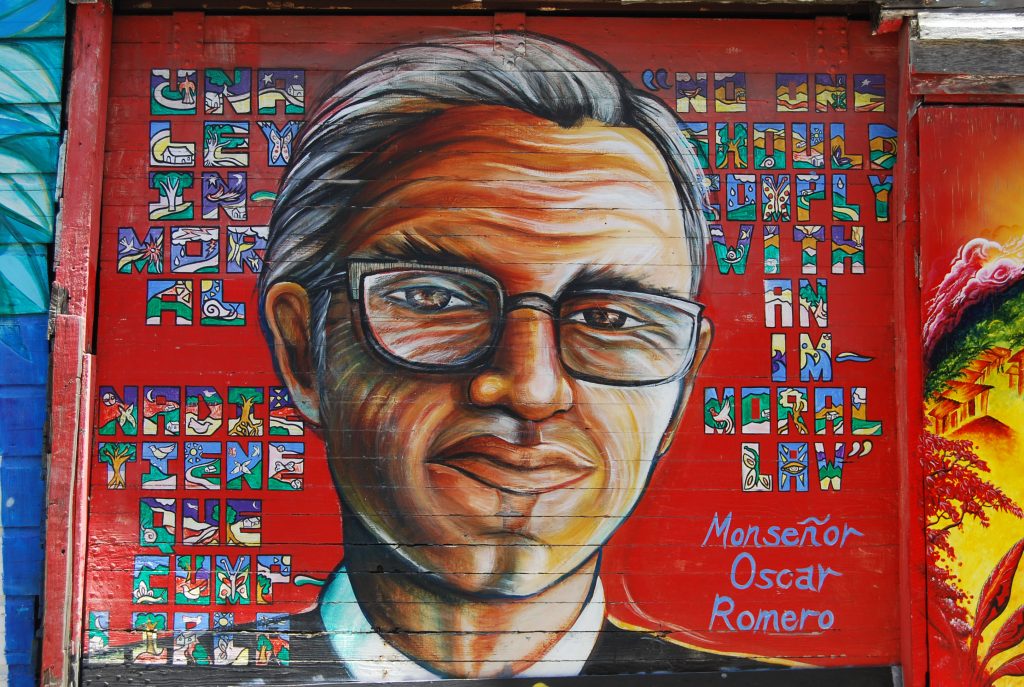

March 24 is the feast of St. Oscar Romero, archbishop and martyr of San Salvador

The selection in 1977 of Oscar Romero as archbishop of San Salvador delighted the country’s oligarchy as much as it disappointed the activist clergy of the archdiocese.

Known as a pious and relatively conservative bishop, there was nothing in his background to suggest that he was a man to challenge the status quo. No one could have predicted that in three short years he would be renowned as the outstanding embodiment of the prophetic Church, a “voice for the voiceless,” or as one theologian called him, “a gospel for El Salvador.”

Nor could one foresee that he would be denounced by his fellow bishops, earn the hatred of the rich and powerful of El Salvador, and generate such enmity that he would be targeted for assassination—the first bishop slain at the altar since Thomas Becket in the 12th century.

Something changed him. Within weeks of his installation he found himself officiating at the funeral of his friend Rutilio Grande, a Jesuit priest of the archdiocese, who was assassinated as a result of his commitment to social justice.

Romero was deeply shaken by this event, which marked a new level in the frenzy of violence overtaking the country. In the weeks and months following Grande’s death Romero underwent a profound transformation. Some would speak of a conversion—as astonishing to his new friends as it was to his foes.

From a once timid and conventional cleric, there emerged a fearless and outspoken champion of justice. His weekly sermons, broadcast by radio throughout the country, featured an inventory of the week’s violations of human rights, casting the glaring light of the Gospel on the realities of the day.

His increasingly public role as the conscience of the nation earned him not only the bitter enmity of the country’s oligarchy but also the resentment of many of his fellow bishops. There were those among them who muttered that Romero was talking like a subversive.

The Church in El Salvador was not the first Church to suffer persecution. The anomaly was that here the persecutors dared to call themselves Christians. Their victims did not die simply for clinging to the faith, but for clinging, like Jesus, to the poor. It was this insight that marked a new theological depth in Romero’s message.

For Romero, the Church’s option for the poor was not just a matter of pastoral priorities. It was a defining characteristic of the Christian faith. “A Church that does not unite itself to the poor in order to denounce from the place of the poor the injustice committed against them is not truly the Church of Jesus Christ,” he wrote.

On another occasion he said, “On this point there is no possible neutrality. We either serve the life of Salvadorans or we are accomplices in their death.”

Once his course was set, Romero followed his path with courageous consistency. Privately, he acknowledged his fears and loneliness, especially the pain he felt from the opposition of his fellow bishops and the apparent distrust of Rome. Constantly he was accused of subordinating the Gospel to politics.

At the same time he seemed to draw strength and courage from the poor campesinos, who embraced him with affection and understanding. “With this people,” he said, “it is not hard to be a good shepherd.”

The social contradictions of El Salvador were rapidly reaching the point of explosion. Coups, countercoups, and fraudulent elections brought forth a succession of governments, each promising reform, while leaving the military and the death squads free to suppress the popular demand for justice.

As avenues for peaceful change were systematically thwarted, full scale civil war became inevitable. In 1980, weeks before his death, Romero sent a letter to President Jimmy Carter appealing for a halt to further military assistance to the junta, “thus avoiding greater bloodshed in this suffering country.”

On March 23, 1980, the day before his death, he appealed directly to the members of the military, calling on them to refuse illegal orders: “We are your people. The peasants you kill are your own brothers and sisters. When you hear the voice of the man commanding you to kill … In the name of God, in the name of our tormented people whose cries rise up to heaven, I beseech you, I beg you, I command you, STOP THE REPRESSION!”

The next day, as he was saying Mass in the chapel of the Carmelite Sisters’ cancer hospital where he lived, a single rifle shot was fired from the rear of the chapel. Romero was struck in the heart and died within minutes.

Romero was immediately acclaimed by the people of El Salvador, and indeed by the poor throughout Latin America, as a true martyr and saint. For Romero, who clearly anticipated his fate, there was never any doubt as to the meaning of such a death.

In an interview two weeks before his assassination, he said, “I have frequently been threatened with death. I must say that, as a Christian, I do not believe in death but in the resurrection. If they kill me, I shall rise again in the Salvadoran people. Martyrdom is a great gift from God that I do not believe I have earned. But if God accepts the sacrifice of my life then may my blood be the seed of liberty, and a sign of the hope that will soon become a reality… A bishop will die, but the Church of God—the people—will never die.”

Romero was beatified on May 23, 2015, at the Plaza El Salvador del Mundo, San Salvador, El Salvador by Cardinal Angelo Amato, representing Pope Francis. He was canonized on Oct. 14, 2018, at the St. Peter’s Square, Vatican City, by Pope Francis himself.

(From R. Ellsberg, “All Saints,” Daily Reflections on Saints, Prophets and Witnesses for Our Time, NY: Crossroad Publishing, 1997, pp. 131-133.)

Source: Licas Philippines

0 Comments