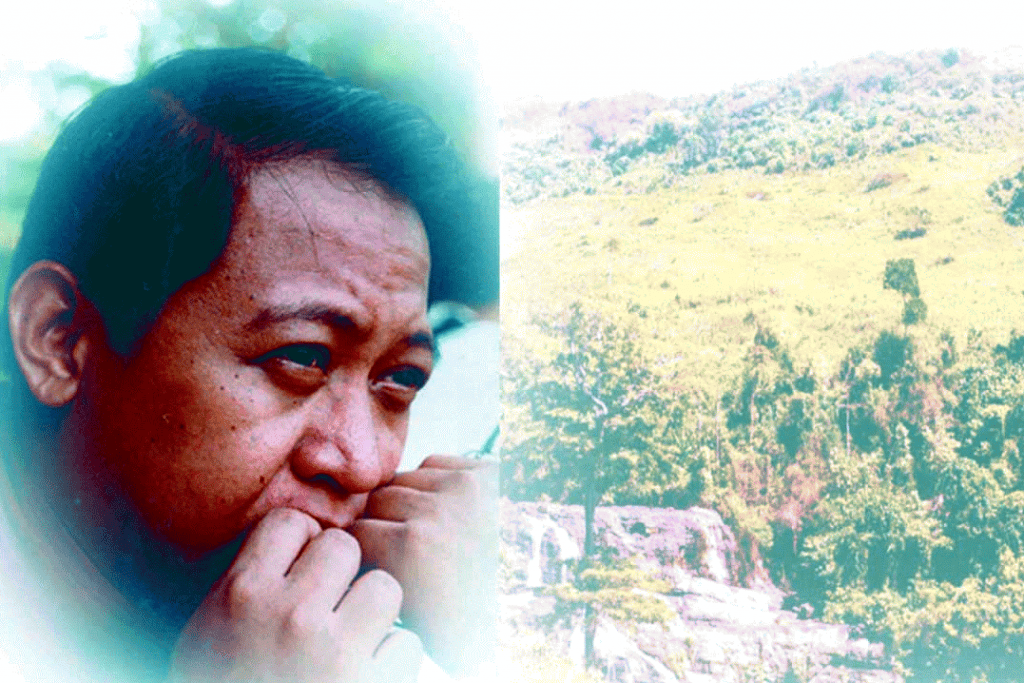

The Prelature of Isabela de Basilan in the southern Philippines launched on Monday, May 3, the cause for the beatification of Claretian missionary priest Rhoel Gallardo, who died while in the hands of the terrorist group Abu Sayyaf in 2000. The following article is a narrative of the last moments of the missionary priest from the book “Into the Mountain: Hostaged by the Abu Sayyaf.”

FOR FOUR DAYS AND FIVE NIGHTS they walked, without eating. They forged their way downhill and then up again, avoiding the sharp rocks and the open roots. They marched in the dark, the rough stones cutting into their feet, the thorns penetrating their clothes, the mosquitoes and leeches feasting on their blood.

They rested during the day, to avoid being spotted by pursuing soldiers, and they marched the whole night, as though wild animals were chasing them.

“Lakad, Father, lakad, malapit nang dumating ang pahinga (Walk, Father, walk. Rest will come soon),” a bandit prodded Father Rhoel from behind as someone else tugged on the rope that was tied around his waist.

Then one of the bandits signaled everybody to stop. The children—tired, sleepy, and wet—wasted no time and dropped to the ground. The older ones moved more slowly, reclining on tree trunks. Even the bandits, hungry and muddy as the rest, were weary. All were wet from the dew and from last night’s rain. There seemed to be no stopping the rain in the forest.

After a few minutes, Ustadz Nur, the bandits’ “operations officer,” ordered everybody to stand up. “We have to move before they come nearer,” he said. Ustadz Nur had been a public school teacher in Basilan before he joined the Abu Sayyaf.

“Do you know what you’re doing?” Abu Amira, the medic, asked, within earshot of Mr. Rubio and other hostages. “Everybody’s tired and we’re not getting anywhere. Where are we heading, anyway?”

“Shut up, Amira,” Ustadz Nur answered angrily. “I know what I’m doing.”

“If I only knew beforehand that we would just walk around and around the forest, I would have not joined this operation,” Abu Amira complained. “Abu Hasser and I could have asked Khaddafy for a vacation.” Abu Hasser was Abu Amira’s younger brother.

“We’re useless in this operation,” the teenage Abu Hasser murmured. “We’re medics and there are no sick people here.”

“Do you really have plans for us?” Abu Amira confronted Ustadz Nur. “You’re just getting us killed.”

“Shut up, the two of you!” Ustadz Nur shouted. “Just get up and walk.”

The stragglers resumed marching. It was Wednesday, May 3.

At around 6 a.m., Ustadz Nur decided to stop. The hostages lay down on the wet grass, ready for a long rest. The day was starting to turn bright, the sun’s rays beginning to penetrate the damp forest.

They had rested for barely 15 minutes when one of the bandits came running back from the front, ordering everybody to move back. “Slowly, move back. Don’t stand up, just move back,” he ordered in a low voice, almost whispering.

“Something must be wrong,” thought Mr. Rubio, who was toying with a stick. “The military must be nearby,” he whispered to Rodolfo Irong, a teacher from Sinangkapan Elementary School, who was sitting beside him. They retreated slowly until they felt their backs pressing against the trunk of a mango tree. Both closed their eyes, resting and thinking of their ordeal.

It had been exactly 45 days since they were kidnapped by the Abu Sayyaf.

Several times during their stay in Mount Punoh Mahadji, the male hostages talked about escaping, especially when they heard from the children that the bandits were planning to hack the older men to death. But they changed their mind after teacher Rosebert refused to join them. “I can’t come with you,” Rosebert said. “My wife Lydda is here and I don’t want to leave her behind.” Nobody argued with him.

Another time they heard rumors that the teachers would be released.

Excitement filled them, but their joy was short-lived, after Father Rhoel talked to the bandits and pleaded for the release of the children instead. The priest also insisted that if ever the Abu Sayyaf released the hostages, he would go last. He was a priest, he said, and he had nothing to lose.

“I will never forget him,” Mr. Irong said to Mr. Rubio once.

“Who?” asked Mr. Rubio.

“Your friend, the priest,” Mr. Irong answered. “He’s something.”

In their six weeks on the mountain, everybody noticed how Father Rhoel spent his time praying. Most of the time, he prayed alone and fervently. Nobody heard the priest complain. At times, he even skipped his food and gave it to the children. And he was always optimistic, confident that everything would turn out fine.

AT AROUND EIGHT IN THE MORNING, the bandits ordered everybody to stand up and start walking again. Lydda observed that they were already out of the forest. She could see that they were in a coconut plantation; she saw a lot of gmelina, lawaan, and mango trees.

Their guards, however, kept moving back and forth. They would order the hostages to move forward, but after a few minutes they would come back and tell them to retrace their steps. “Are we lost?” Lydda asked her husband Rosebert.

At around 8:30, the bandits again let the hostages rest and gave them young coconuts for breakfast. Bananas were also distributed, and the children devoured it in their hunger.

After eating, the group moved again. They moved from one place to another, from one hill to the next. They did this the whole morning, walking as if in circles, until they reached a slope where there was a lot of coconut trees and some kind of shrub that grew tall but had a lot of thorns. Nearby a creek was flowing, a treat for the thirsty hostages.

Mr. Rubio saw Abu Sabaya use a cellular phone. “If this takes longer, it might be difficult for us to leave Basilan,” he heard the bandit telling someone on the other end of the line.

Five hostages—Father Rhoel, Ruben Democrito, Mr. Rubio, Rosebert, and Lydda—sat together around a small tree with thorns. By then it was already noon, and the hostages distributed small balls of rice and slices of cooked string beans to each hostage. The children swallowed everything and satisfied their thirst at a nearby spring. The older hostages, however, were not allowed to stand up. Instead, the bandits told the children to fetch water for their teachers.

After eating, the male hostages were bound together in twos. When a bandit approached Mr. Rubio, the school principal offered his right hand, thinking that, whatever happened, he could still use his left, which the bandits allowed free because “the old man had a hard time walking.”

The bandits tied Mr. Rubio back to back with Mr. Irong, both of whose arms were bound. Father Rhoel was paired with Ruben, while Rosebert was roped to a B-57 shell and then moved to the upper slope with his wife.

Lydda sat under a tree while her husband lay on the ground beside her. The bandits rested on the lower slope a few meters below Father Rhoel, Ruben, Mr. Rubio, and Mr. Irong.

Everyone tried to get some rest—except the children, who enjoyed playing with the younger bandits. Some of the younger Abu Sayyaf climbed the coconut trees and tossed the coconuts down to the children, who in turn distributed it to everyone else.

Khaddafy Janjalani, Abu Sabaya, and the other Abu Sayyaf leaders sat nearby, talking earnestly. Abu Jandal bathed himself in the nearby creek, while Abu Jar, Abu Bilog, Abu Hapsin, and Abu Mahamdi exchanged jokes with the children.

After eating the coconuts and drinking its water, the teachers and some of the bandits lay down to sleep; the children continued playing.

Lydda watched Father Rhoel, Ruben, Mr. Rubio, and Mr. Irong trying to catch the shade of the shrub. As the heat rose, the four men tried to adjust themselves to avoid the sun. Lydda smiled to herself. “These old men are acting like children,” she thought.

By two in the afternoon, Mr. Irong, who was wearing two sweatshirts, could not stand it anymore. He called Kipyong and Ryan Laputan, another of the children-hostages, and asked them to loosen his knot so that he could remove his shirt. The guards were just a few meters away, but they were not watching.

“Why did you tie them up?” Lydda asked a bandit who was sitting nearby.

“We don’t want them to escape,” he said.

“Why didn’t you tie us up too?” she asked, just to make conversation. Her husband seemed to be already asleep beside her.

“You don’t know where to go,” the bandit said.

Nearby, Anabelle told Chary not to go too far. “Don’t leave Cristy and Romela,” she said. “Take care of them, ha, Chary?” Anabelle was sitting with her sister Romela nearby.

“Yes, auntie,” Chary answered, nodding her head. She was sitting on the grass with her younger sister, Cristy, sleeping on her lap.

Father Rhoel turned his head. “Don’t leave each other,” he told them. “Whatever happens, always stay together.”

“Chary, you take care of your sister. Don’t be afraid,” the priest said. “When we get back home, I will bring all of you to Jollibee in Zamboanga. We will have hamburger,” he promised, smiling.

Abu Jaber and Abu Mahamdi went near Chary.

“You leave the children alone,” Anabelle warned. “They won’t bother you.”

“Where are we going?” Chary asked Abu Mahamdi, who had already become her friend.

“We’re going to Sulu. A boat is waiting for us on the beach,” the bandit answered.

“I don’t want to go to Sulu,” Cristy said, opening her eyes.

“Don’t worry, Cristy. We will release you there and you can go home to your families,” Abu Jaber assured her.

(To be continued tomorrow)

Source: Licas Philippines

0 Comments