My fellow Filipinos,

As the bloodstained curtains slowly begin to close on the current regime, allow me these words.

For a good many of us, it had been a tough five years. No, let’s make that grueling. In fact, exhausting. Harrowing. And that’s on a good day.

Filipinos have been promised a Nirvana that never materialized, a paradise built on dolomite sands. A day or two of the habagat and it’s all trash. Forget six months.

Why? Because for all that dolomite looks good, the builders couldn’t care less if it survives a day of rains or not. What was important was what they could siphon off from the Php389 million spent to “rehabilitate” the historic Manila Bay.

Let’s not kid ourselves any more than we have to: what this administration had done in the last five years hardly consisted of the stuff legacies are made of. Each attempt was a punchline in a series of jokes that made this current administration the laughingstock that it truly is.

It came to a point where it wasn’t funny anymore in light of the trillions in loans this administration will leave us to experience like a crown of thorns on our heads. Generations of our children will be shelling out for these loans either with their lives or the bruises on their hands and feet, slaving day and night for those who couldn’t care less if our children live or die.

The more than 30,000 murdered in Duterte’s bogus drug war, and the thousands more harassed, intimidated, persecuted and illegally detained, only made matters more unbearable, if not altogether unspeakable.

The fight was fierce. It took every ounce of courage and tenacity to push back. The Duterte regime retaliated with more lies, more harassment, police raids that led to the murder of activists and farmers, and the illegal detention of journalists, and the passing into law of a bill which brands critics as terrorists.

“There is no crueler tyranny,” Baron de Montesquieu once said, “than that which is perpetuated under the shield of law and in the name of justice.”

All this made for turbulent politics where many have been party to corruption and many others to wholesale murder. It wasn’t Duterte’s intention to build a nation, that much is certain now. He had every intent of crushing it.

And for what purpose you may ask? Narcissistic people hardly need any justification for their whims, save that they can and they will.

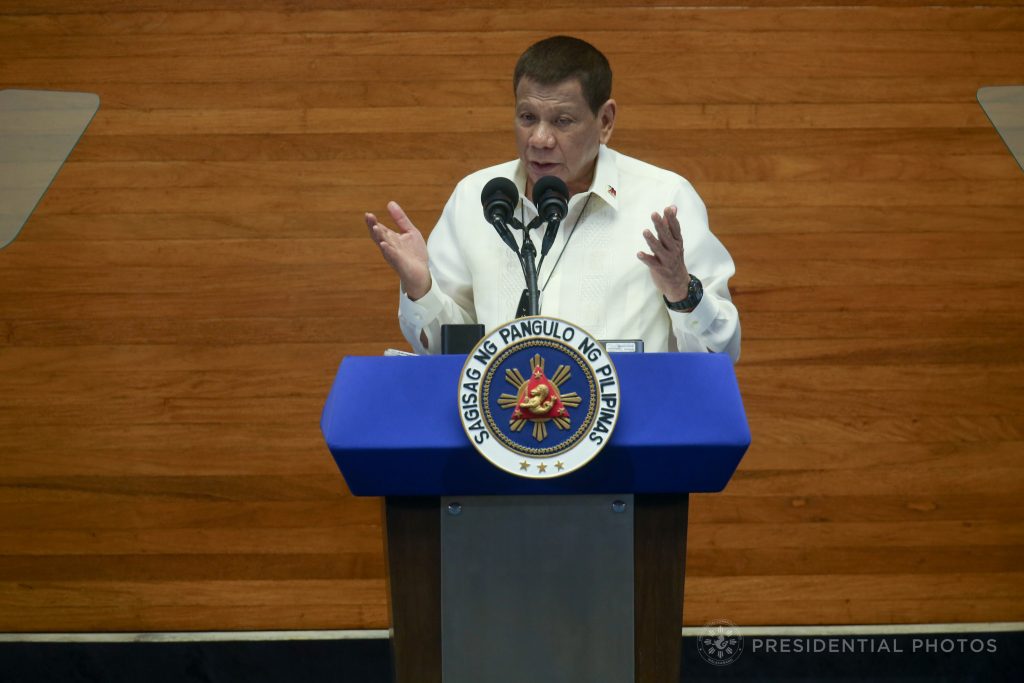

Today, at his final State of the Nation Address, Duterte will do everything in his power to persuade the Filipino people that he will be leaving us a legacy of which we can be proud. His spin doctors will rehash every figure, reinterpret every statement, to mean just that.

His army of paid trolls would be unleashed on a populace who had had enough of his lies. Social media would again be the site of a fierce battle for hearts and minds. It’s a campaign whose aftermath may dictate the outcome of the 2022 elections, if an election would take place.

All this fielding of candidates, this fracas with supposed “political allies-turned-rivals,” may just be another ruse to keep us off guard, to miss the last strategy in the Marcosian playbook: the declaration of martial law.

Tyrants do not give up power that easily—not even to allies. To them, the only power worth wielding is the power in their hands. Every other kind is pointless.

However, do not mistake power for strength. If there is one group of people who has exhibited more strength than can be imagined, outside our brave activists, are the journalists.

Since that fateful day in July 2016 where Duterte sparked an ongoing inquisition against Filipino journalists, when he said, “Just because you’re a journalist you are not exempted from assassination, if you’re a son of a bitch,” the battle since then has gone from shadow boxing to full contact.

Faced with the daily risk of intimidation, illegal arrests and detention, the possibility of infection due to the pandemic, retrenchment and poverty, charges of libel or terrorism, and the looming threat of being the target of assassinations, our journalists couldn’t care less about all these things for as long as the job requires them to be where they ought to be: right in the middle of where it is happening.

Thus began the systematic persecution which left a little over 20 journalists dead in just five years, while hundreds of others suffered harassment, intimidation, threats, and illegal arrests, including journalists on campus.

On Feb. 7, 2020, Frenchiemae Cumpio, executive director of the Eastern Vista news website and a radio news anchor at Aksyon Radyo-Tacloban DYVL 819, was arrested during a series of police raids in Leyte Province. As of this writing, she remains in jail.

The refusal of this administration to grant ABS-CBN a renewed franchise forced the laying off of 4,500 media workers based on the figures culled by the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP). This left many far-flung provinces without access to news and information.

Rappler faces 13 legal cases against it, to say little of the ongoing ban on Rappler correspondents to cover presidential events. The legislative warfare against journalists and critics of government built a formidable fortress in the passing into law of the Anti-Terrorism Bill last year.

The recent death of Nonoy Espina, former NUJP chairperson and fighter for the rights and welfare for the press, due to cancer saw the creation of the Nonoy Espina Emergency Fund for Media Workers in honor of its former head.

Nonoy was well aware of the reality on the ground: the pandemic, coupled with continuing harassment, retrenchment, and closure of their respective newsrooms, have all but crushed the lives of many journalists.

According to the NUJP’s latest stats, 7 in 10 journalists take on other jobs and ventures to make ends meet. Roughly 4 in 10 Filipino photojournalists earn only about P2,500 monthly salary due to Covid-19.

And yet despite the overwhelming crisis journalists are forced to face each day, these newshounds soldier on, braving harassment and infection. As for those infected by Covid-19’s newest Delta variant, the NUJP has created the Tabang Media (Help for the Media), “a fundraiser and peer support program for fellow media workers struck by the virus”.

The problem is actually more excruciating than it sounds. With the administration making it harder and harder for journalists to gather and vet information, a life forced to scrounge the bottom of the barrel doesn’t help in empowering an already struggling press.

The stakes are high. Much too high, in fact, that journalism in the Philippines has become one, if not the most dangerous profession next to traversing the highwire without a net.

NUJP itself, whose efforts to assist fellow journalists have been largely laudable, has been red-tagged continuously by the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC). This puts their members at risk of being killed.

Where journalism is deemed a crime as heinous as terrorism, there can only be one conclusion: that the regime who wishes to oppose the truth can only wish evil upon the nation.

That is why to be a journalist these days is to live dangerously. Henry Grunwald, editor of TIME magazine, once said, “Journalism can never be silent: that is its greatest virtue and its greatest fault. It must speak, and speak immediately, while the echoes of wonder, the claims of triumph and the signs of horror are still in the air.”

The real state of the nation cannot be divorced from the state of our rights as free citizens. The last five years under Duterte have been a continuing attempt to crush our rights to life and speech, dragging even the right of a free press into the fray.

No amount of sociopolitical and economic advancement—however real or imagined—can outwit a profession with a fighting tradition and a solid ritual of banding together whenever push comes to shove.

Outgunned, but never without hope, our journalists not only took the blows as any good boxer in the ring ought to do in order to remain on his/her feet, it hurled its own punches in the face of lies, fake news, and all obsolescent reinterpretations of history.

In 2016, Duterte picked a fight and our journalists gave it to him, telling him to bring it on. Sooner or later, one has got to go.

In the final analysis, journalists and the public are one and the same. The flesh and blood of facts protect the soul of every Filipino’s right to know.

This makes our fight—the people’s fight—the true state of the nation. And fight we shall, from now till 2022.

Joel Pablo Salud is an editor, journalist and the author of several books of fiction and political nonfiction. He is currently the chair of the Philippine Center of International PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official editorial position of LiCAS.news.

Source: Licas Philippines

0 Comments